WASHINGTON — With 20 world leaders in town for 24 hours, there wasn’t much time for grand gestures or bold promises at Saturday’s summit meeting on the global financial crisis. But that did not stop the leaders from bringing 20 different agendas, some more ambitious than others.

There was the French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, without his glamorous wife, Carla, but with a raft of proposals to “change the rules of the game,” as he said last week after a meeting of European leaders.

There was Hu Jintao, the president of China, heading a delegation of 100 people and wielding a fat checkbook — nearly $2 trillion in foreign exchange reserves — that Beijing could lend to distressed countries.

There was Prime Minister Gordon Brown of Britain, emboldened by his much-praised response to the banking crisis at home, and fresh from criticizing the proposed bailout of American carmakers in a speech in New York on Friday.

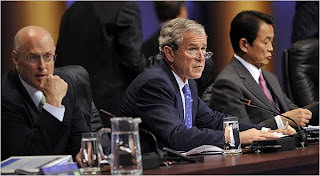

And finally, there was President Bush, the reluctant host in his waning months in office. “The crisis was not a failure of the free-market system,” Mr. Bush said in his weekly radio address on Saturday, trying to dial back expectations. “The answer is not to try to reinvent that system.”

How world leaders approached the Summit on Financial Markets and the World Economy — as Mr. Bush designated the meeting — had a lot to do with how the financial crisis affected their political fortunes.

For Mr. Bush, the upheaval delivered a final blow to an administration staggering under an unpopular war in Iraq and a weakening economy. With President-elect Barack Obama watching from Chicago, Mr. Bush was not even the most sought-after American at the meeting he organized, a meeting that was the idea of Mr. Sarkozy’s. Instead, leaders from Mexico to Turkey lined up to meet two emissaries sent by Mr. Obama.

Mr. Sarkozy, on the other hand, only became president of France last year, after the seeds of the crisis had been planted. His call for greater regulation plays into France’s historical preferences for a robust state role in the market, making Mr. Sarkozy an ideal point man for the effort.

“Sarkozy is in a very strong position of not owning the crisis, as other leaders do,” said Kenneth S. Rogoff, a professor of economics at Harvard. “Like Obama, he can take a more detached view.”

The French leader’s high profile was not without risks. “This was his idea,” said Simon Johnson, a former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund.

Besides Mr. Sarkozy and Mr. Bush were the leaders from Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Britain, Canada, China, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, and Turkey.

Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, and President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner of Argentina were the only two women in the Group of 20 meeting — and neither, analysts said, brought a very strong hand.

The German economy just slipped into recession, and its government was slow to accept the need to recapitalize its banks, which purchased a lot of toxic mortgage-related assets from the United States.

Argentina, meanwhile, announced it would nationalize $26 billion of private pension funds, raising fears that the government was short on cash and putting Mrs. Kirchner into an economic dog house with foreign investors, who are pulling their money out of the country.

The Russian president, Dmitri A. Medvedev, also came with arguably reduced influence, partly for economic reasons: as the price of oil has plummeted, so has Russia’s economy, its foreign exchange reserves and perhaps some of its political muscle.

None of this has stopped Mr. Medvedev from striking a combative tone toward the United States.

“They let this currency bubble grow in the interests of stimulating domestic growth,” he declared in a recent speech. “They did not listen to the numerous warnings from their partners, including from us. As a result they have caused damage to themselves and to others.”

For Mr. Brown of Britain, the crisis has been a mixed bag. As chancellor of the Exchequer under Tony Blair, Mr. Brown is identified with the economic policies that gave Britain years of growth but some of the same excesses as in the United States.

However, by moving quickly to recapitalize the British banking system, Mr. Brown appeared decisive and won praise from economists. He also stopped, at least for now, a stream of political obituaries suggesting he would soon be ousted by the Tory leader, David Cameron.

On Friday, Mr. Brown was introduced at a breakfast at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York by Robert E. Rubin, the former Treasury secretary, with lavish praise for his role during the crisis.

“Not only the U.K. but the entire world has been very fortunate to have you as a leader,” Mr. Rubin said.

Mr. Brown, smiling broadly, responded that he was “pleased to say that a large number of governments around the world have recognized” that injecting capital into banks is the best way to restore stability.

The prime minister felt confident enough to offer the United States some unsolicited advice, obliquely criticizing proposals supported by Mr. Obama to bail out the Big Three automakers.

Without referring to the companies by name, he warned against calls to save jobs in industries that were facing an irreversible decline in the face of global competition. The right response, he said, would be to say, “We can’t help you keep your old job, but we can help prepare you for your next job.”

To help countries hurt by the crisis, Mr. Brown is pushing for the resources of the International Monetary Fund to be expanded. The fund, he said, should function like an “international central bank.”

The trouble with this idea is that there are only a handful of candidates with enough cash to pour money into the I.M.F. — China, Japan, and oil producers like Saudi Arabia. The Japanese prime minister, Taro Aso, pledged up to $100 billion in additional lending to the fund.

To persuade these countries to increase their contributions would require giving them a larger role in the governance of the fund. And that would mean reducing the influence of Britain and other European countries.

China staked its claim to a significant role in another way: It announced a $586 billion stimulus package a week ago, allowing President Hu to seize the initiative on economic policy.

For leaders of emerging-market countries who have been clamoring for a seat at the summit meeting table, even being here was something of a victory. For the president of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, it was partly a simple matter of protocol: Brazil currently leads the Group of 20, which gave Mr. da Silva some say over the agenda.

Beyond that, he has been outspoken about how developing countries are victims of a crisis not of their own making.

“No country is safe,” Mr. da Silva said last weekend, opening a preparatory meeting of finance ministers in São Paulo. “They are all being infected by problems that originated in the advanced countries.”

Pakistan Agrees to I.M.F. Loan

KARACHI, Pakistan (AP) — Pakistan has agreed to borrow $7.6 billion from the International Monetary Fund to try to avoid an economic crisis, an official said on Saturday.

Shaukat Tareen, Pakistan’s finance chief, said the I.M.F. had agreed “in principle” to the bailout after vetting government plans to tackle Pakistan’s growing budget and trade deficits.

The loan will shore up Pakistan’s foreign currency reserves and help alleviate the prospect of a run on the rupee and a default on international debt.

Steven Lee Myers contributed reporting from Washington, and John F. Burns from New York.

Source: msnbc

10:40 PM

10:40 PM

Posted in:

Posted in:

0 comments:

Post a Comment